Can I ask you for a favour?

Yes, yes, yes.

This friend, who I love, whose brow I could draw from memory, is sitting cross-legged on my couch. I’ve placed a cup of hot tea in her hands and tucked a throw blanket around her curled toes, against the draught in my apartment. It’s a hard season. The days darken quickly and the wind makes our eyes water and our late twenties bring sharp, painful shifts. She’s describing this heaviness she’s been feeling and, instantly, as she explains its weight, I feel it too, an urgent tug at my sleeve. I rest my hand on her sleeve, at the crook of her elbow. Why didn’t you say something sooner, so I could share this with you? I didn’t want to burden you.

I know this feeling well. I know you do too. But in the morning, when I swing my legs over the bed and my feet search for my slippers, I choose to connect. To live beyond my comfort and into the paths of my partner and my sisters and my friends. What good would it be if we only ever walked alongside our friends when our sidewalks were paved in the same direction? When it was only ever the comfortable way? How many conversations we would miss, how many stories, how many secrets. How hard-shelled we would become. How little we would come to be known by those who make us whole. How little we would know them.

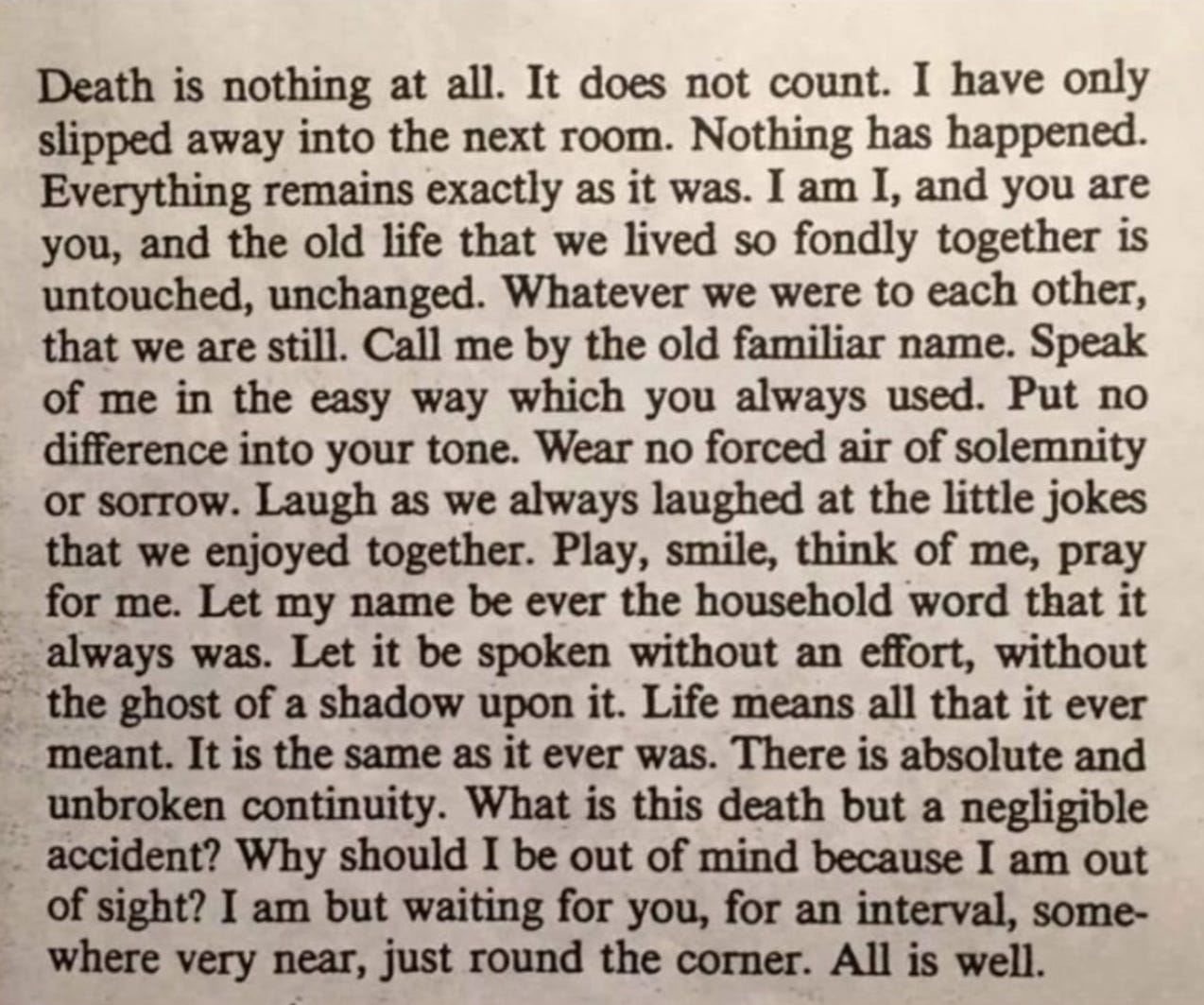

While imprisoned at Reading Goal in England—charged with the crime of being in a same-sex relationship in 1895—Oscar Wilde was not allowed to write his usual plays or novels. Inmates were, however, allowed to write letters. Wilde therefore wrote De Profundis (Latin for “from the depths”), a long letter to his lover, Lord Alfred Douglas. In it, Wilde writes:

If after I am free a friend of mine gave a feast, and did not invite me to it, I should not mind a bit. I can be perfectly happy by myself. […] But if after I am free a friend of mine had a sorrow and refused to allow me to share it, I should feel it most bitterly. If he shut the doors of the house of mourning against me, I would come back again and again and beg to be admitted, so that I might share in what I was entitled to share in. If he thought me unworthy, unfit to weep with him, I should feel it as the most poignant humiliation, as the most terrible mode in which disgrace could be inflicted on me.

This is the world we daydream of, within which our children can be raised—where I am burdened by you, and you, by me. When did we commodify this? Sorry, I don’t have the capacity for this right now. Sorry, my cup is full. Sorry, no room for you, I’m too comfy here. When did we come to believe everything is balanced? Transactional? Tit for tat? Some days, I have more. My supermarket tulips are blooming, the herbs on my counter are abundant, and my butter is salty and spreadable. What good is it to me if I cannot have you over, spread it on a piece of warm toast, and offer you half?

I would love to do a favour for you. What is this, if not an endless giving, of favours and gifts and time, and an endless taking too, of holding and sorrows and wine? When I say I would go out of my way for you, I mean to say: my way is quiet and dull without your laugh. Let’s go the long way together. I hope I can look back and say I did more than endlessly prioritize my own comfort. What are we if not a collection of little sacrifices, over and over, until we have a family?

Yes, I will drive you to the airport. I will set my alarm an hour earlier in the morning, drink an extra coffee in the afternoon, to be on time for you. To wave goodbye and tell you see you later and then, to see you later. Yes, I will help you move out of the place we shared meals at the kitchen table, into a new home, with a new table. Both our backs will ache the next morning and I will be stamped into a chapter in your book and isn’t that so lucky? No, I can’t fix it but yes, I will share it with you. I would rather take your pain in my own hands than let you sit with it alone, a million times over. I will cry with you. Let me cry with you, please?

And then, also, to let myself receive in return. With loving must come being loved. I know that an endless give without receive is just emptiness. To let those who love me put out the good plates and cook the meal that fills me. Stay up late to watch my favourite movie, give me the same reminders over and over in pursuit of my healing. This is not a burden, this is living. Hear me again. This is not a burden, this is living.

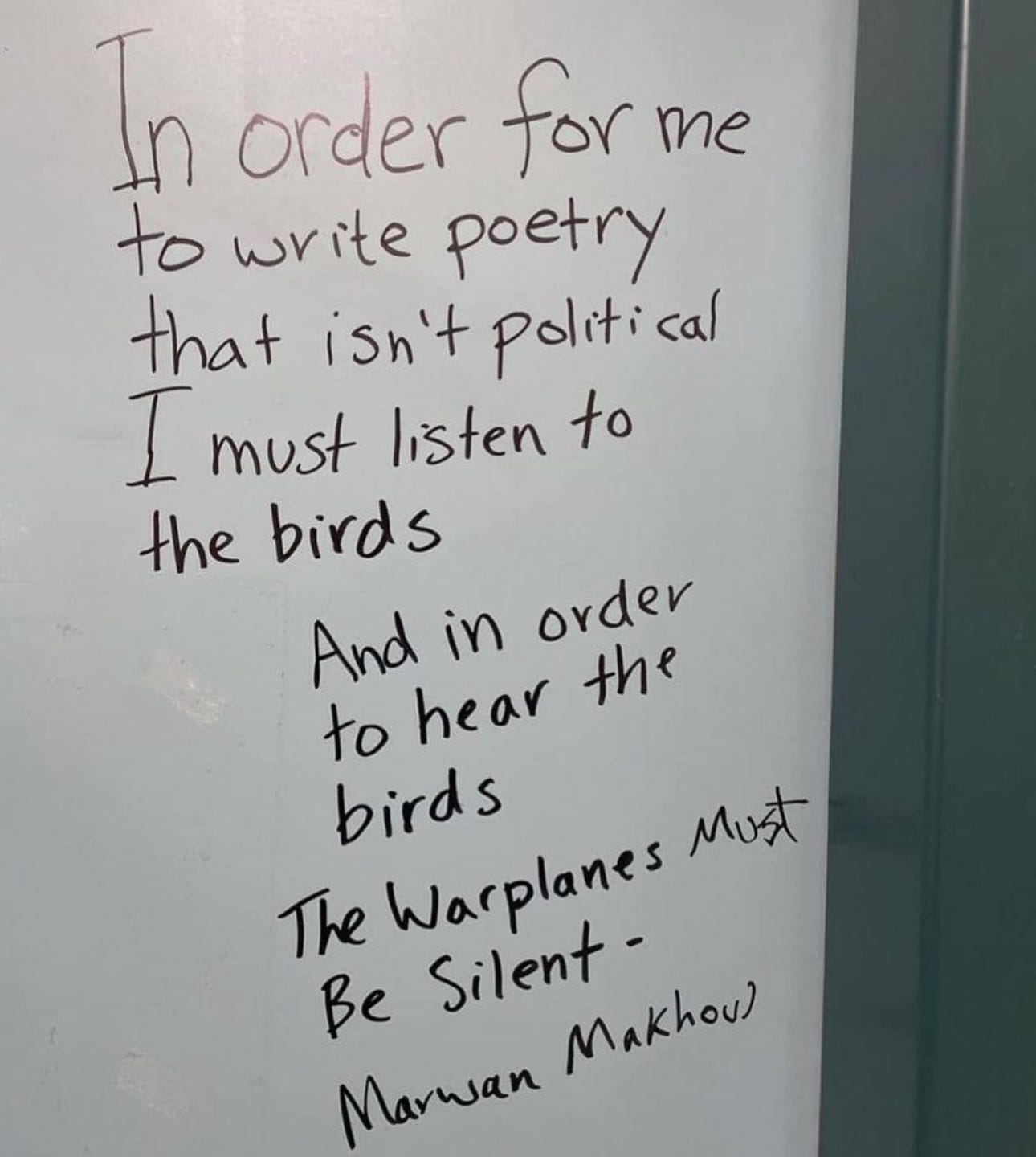

You cutting my onions for me and me peeling your garlic. This is standing in the January cold and rallying for a free Palestine with you, finding your eyes in the sea of hundreds. This is the image of the world we dare to imagine. This home, our daily walk in the neighbourhood, you going half a mile in the wrong direction just to see me home—a picture of what we wish for the world.

The world can be remade in the image of my table. All mouths, fed. All shoulders, touching.

(Inspired by the above excerpt from Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis and this post.)

It’s so nice to be back here with you. I plan to be more consistent in this space, but what’s life if not always getting in the way of our plans?

Thank you, as always, for being here, right on time. I love having you here. If you enjoyed this little love letter, I want to know! Shoot me a message on Instagram: @ramnasafeer. If you have another question or comment or sweetness to share, you can also send me an email at ramnasafeer@gmail.com. Let’s chat!

I hope you stick around. Sending love and rest,

Ramna

So excited for more letters!